Inclusive practice

What is inclusive practice?

Inclusion is a process that helps overcome barriers limiting the presence, participation and achievement of learners.

Equity is about ensuring that there is a concern with fairness, such that the education of all learners is seen as having equal importance.

– UNESCO. (2017) A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education

Inclusive pedagogy is focused on including all students in learning. The aim is to bring students together and build a classroom community where every child is valued and is able to reach their potential.

This means:

- shifting your focus from students identified as having "additional needs" to the learning of all students in the classroom

- rejecting the idea that student ability is fixed and that the presence of some will hold back the progress of others

- seeing difficulties in student learning as a professional learning challenge to develop new ways of working, rather than as a deficit in the learner.

"...providing rich learning opportunities that are sufficiently made available for everyone, so that all learners are able to participate in classroom life. By focusing on what is to be learned by the community of learners in the classroom, the inclusive pedagogical approach aims to avoid the problem and stigma associated with marking some learners as different."

Inclusion and The New Zealand Curriculum

Inclusion is one of eight principles in The New Zealand Curriculum. The principle of inclusion applies to all students in all New Zealand schools. Knowing your students is key to creating a more flexible environment that supports all learners, where barriers to learning are minimised.

"The curriculum is non-sexist, non-racist, and non-discriminatory; it ensures that students’ identities, languages, abilities, and talents are recognised and affirmed and that their learning needs are addressed."

Principles of inclusive pedagogy

Inclusive practice is often focused on students with exceptional needs. Generally it's about how to differentiate instructional material in order to include these students with their same grade peers. Inclusion is not just about students with diverse or "special" needs. It is about considering all students including: cultures, identities, languages, and abilities.

Inclusive pedagogy:

- rejects the practice of designing educational experiences on assumptions of fixed ability and predictions of potential

- is opposed to practices that address education for all by providing additional or different experiences for some

- views diversity between children as natural, but also assumes children have a lot in common.

Build an inclusive classroom by:

- providing a range of options which are available to everybody

- responding to difference in ways that respect the dignity of each child in the classroom

- taking responsibility for all learners

- working with colleagues and resource teachers to identify successful ways of approaching the difficulties in learning faced by children.

Using digital technologies to remove barriers and support all learners

In an inclusive classroom the contributions of all students, their families/whānau, and communities are valued. Every learner is recognised as unique and their languages, cultures, and interests inform classroom organisation and planning for learning. Barriers to participation and achievement are identified and removed.

Planning for all students

Planning for all students needs to be the foundation rather than planning “for some” or “for one”. By focusing on what is to be learned by the community of learners in the classroom, the inclusive pedagogical approach aims to avoid the problem and stigma associated with marking some learners as different.

Begin by knowing your learners

Learner profiles support you to:

- identify students strengths

- identify students' learning needs

- involve parents and whānau.

Learner profiles are designed to help you plan instructional activities and provide materials that will support your students to effectively access the classroom curriculum. Learner profiles can be created collaboratively with students and parents, and in any format, including:

- document with photos

- PowerPoint presentation

- video

- blog

Planning teaching and learning programmes

Identify what:

- students can do independently

- students can do with peer support

- digital technologies/tools will support learning.

Effective teachers use a range of assessment data to differentiate the curriculum as needed and engage learners in purposeful learning through a range of media and resources.

Dimension 2: Frameworks and evaluation indicators for ERO reviews

Consider how you can create learning opportunities that all students can participate in.

- Identify barriers to student learning.

- Extend what is ordinarily available for all learners, rather than using teaching and learning strategies that are suitable for most alongside something additional or different for some who experience difficulties.

- Focus on what is being taught and how you are teaching it rather than who is to learn it.

- Believe that all students will make progress, learn, and achieve.

- Focus teaching and learning on what students can do rather than what they can not do.

- Use a variety of grouping strategies to support everyone's learning rather than relying on ability grouping to separate "able" from "less able" students.

- Use formative assessement to support learning.

- Inquire into new ways of working to support the learning of all students.

- Work with other teachers and support staff to respect the dignity of students as full members of the classroom community.

- Commit to ongoing professional development as a way of developing more inclusive practices.

- Use strategies to focus on all learners, rather than most or some.

Teacher, Kate Friedwald explains how she uses a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach in her classroom at Wairakei School. Teaching is based on students' specific needs and learning activities are differentiated and personalised for each learner.

Getting the students' perspective

Your students will have a unique perspective on learning and teaching. Ask them the following questions and gather the information to find out what they think about inclusion. Use this to inform your approach to creating an inclusive classroom, where everyone belongs.

- What does belonging mean in our class?

- Does belonging matter to your learning?

- How are the children similar to each other in our class and how are they different?

- Does being similar or different matter to your learning?

Consider the environment

"The key challenge facing teachers who wish to become more inclusive in their classroom practices is how to respect as well as respond to human differences in ways that include learners in, rather than exclude them from, what is ordinarily available in the daily life of the classroom."

Classroom climate

- Create a comfortable and safe classroom community.

- Embed learning as a collective endeavour.

- Nuture mutually supportive relationships.

- Promote shared behaviours and values.Teaching/Inclusive-classrooms

Physical environment

- Consider how a solution for one student can be offered as an option for everyone.

- Provide timetables that students can see and access easily – these could be online and displayed.

Wairakei School teacher, Kate Friedwald explains how information and feedback presented visually and orally in her digital classroom are designed to meet the learning needs of Daniel, a student with ADHD. This way of setting up the classroom environment means Daniel can participate fully in the classroom programme and access information easily. The modifications made to include him support all students in the classroom.

Key resource

Developing an inclusive classroom culture

This guide for teachers provides strategies and suggestions for developing an inclusive classroom that:

- values the contributions of all students, their families/whānau, and communities

- recognises that every learner is unique and builds on their languages, cultures, and interests

- identifies and removes any barriers to achievement.

Using digital technologies to create an accessible curriculum

Consider how you can use digital technologies to:

- develop a more inclusive learning environment

- ensure all students have equitable access to the classroom curriculum

- meet the needs of diverse learners within the classroom learning environment

Use digital technologies to create multiple learning pathways

Having multiple learning pathways helps to foster motivation in students because their interests and strengths are used as a vehicle for exploring new concepts and reinforcing learning.

Using apps to support student learning

Reading

“Robbie had lost interest in reading. He was a past reading recovery student and had plateaued in the classroom. I had noticed that he particularly enjoyed working on the iPads and worked hard to gain reward time on the devices. In term two I introduced him to some extra activities for him to do at reading time.

- He read onto Quick Voice (daily), listened to his recording, and looked for his next steps.

- He listened to or read an e-book on the iPad (daily).

Within a couple of weeks I noticed, Robbie was totally independent in doing these tasks and really enjoying being read to. His enthusiasm for reading increased and a positive attitude towards group time and home reading was the result.”

Writing

“A child with learning difficulties, who finds writing hard work, used My Story to dictate and write a story. He was able to share his work with the class. The class enjoyed the story so much that they made suggestions about what could happen next etc. His chest puffed out and his head visibly swelled!”

– Teacher

Tools you could use

"[Using a laptop] is the best thing that ever happened to me......I’ve been able to actually complete my work and generally just have a good time."

- Text to speech tools – introduce students to alternative ways of accessing text if they have difficulty reading.

- Speech to text tools – dictation features allow students to talk into digital devices and have the text 'typed' as they speak.

- Story writing tools – such as Book Creator and Storybird removes the barriers created when writing by hand.

- Mindmaps to support planning – such as Popplet, Coggle, and MindMup can support students with organising their ideas. Students can use either images or text.

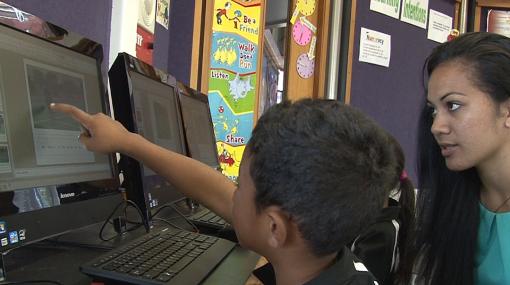

Felix is a Year 5 student with dyslexia at Wairakei School. He explains how he uses iPad apps like IWordQ to make the process of reading and writing easier.

Differentiation and adaptation

What is differentiation?

"Differentiations are changes to the content of the school and classroom curriculum and expected responses to it. These changes support students to experience success."

What is adaptation?

"Adaptations are changes to the school and classroom environment, teaching and learning materials, and associated teaching strategies. These changes support students to access and respond to the school and classroom environment."

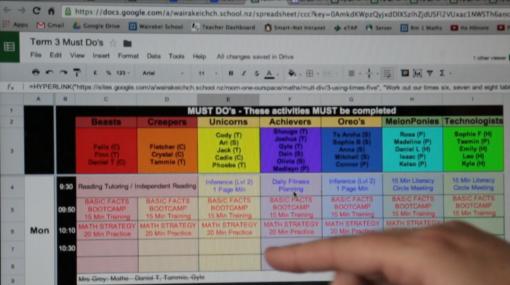

Wairakei School teacher, Kate Friewald describes how she uses Google Docs to support differentiated learning in her classroom. She uses Google spreadsheets to create her weekly plan, maths plans, and literacy plans. She shares these with students based on a "must do/can do" process. Students are split into cooperative work groups, not necessarily structured on reading or maths ability. Each group member has a number of "must dos", to complete within the morning block, and some blank time to structure their own learning focused on their learning needs.

Within a flexible learning environment, where barriers to learning have been minimised and supports and options made available to all, there will still be a need to differentiate learning for particular students in specific contexts.

Consider how you could use digital technologies to answer some of these questions as you plan to meet the needs of your students:

- Would technologies help some/all students?

- Do some students need material presented differently?

- Should some students present their work differently?

- Will all students be assessed in the same way?

- Will some students need additional or different goals?

Personalising learning

In deep expressions of practice, students' learning activities and the curriculum/knowledge content they engage with are shaped in ways that reflect the input and interests of students, as well as what teachers know to be important knowledge.

Supporting future-oriented learning and teaching – a New Zealand perspective

It is important not to confuse individualised and differentiated learning with personalised learning.

Personal learning or instruction is a method of teaching that tailors learning for each student's strengths and motivations, needs, and interests –including enabling student's voice and choice in what, how, when, and where they learn – to provide flexibility and supports to ensure mastery of the highest standards attainable.

Basye, 2014; Bray & McClaskey, 2014; iNACOL, 2016; Patrick, Kennedy, & Powell, 2013 in Ntuli, 2017

Personalising learning allows akonga/students to take control of their own learning. In a personalised learning environment, students can articulate the how, why and what of their learning. Student voice is expressed and encouraged, while learning goals – and the means of achieving those goals – are co-constructed by students and teachers.

When learning is personalised, students:

- understand how they learn

- own and drive their learning

- are co-designers of the curriculum and their learning environment.

At St Hilda's Collegiate, every Year 9 student is mentored with someone from the local community and they work throughout the year on their Passion project.

Personalised learning | Using digital technologies to support personalised learning |

| Students drive their own learning. | Students have options when deciding on their own student inquiries, or are prompted to define their inquiries and content areas themselves. They are encouraged to select tools that support them to realise their learning goals. Teachers act as facilitators and guides for learning and reflection. |

| Learning is connected with interests, talents, passions, and aspirations. | Students are given choices in their learning and are encouraged to explore their passions. Teachers need to know their students. Using digital technologies enables students to take learning beyond the classroom and choose the best medium for constructing and sharing their learning. The Impact project – Miranda Makin, DP Albany Senior High School explains, the purpose for us was to utlilise the opportunities digital tools afforded to collaborate online and to get feedback. |

| Students actively participate in the design of their learning. | Students can provide explicit feedback to teachers on units and projects, and have input into their classroom curriculum. Students manage part or all of their timetable, which is accessible online and shared with the teacher. School timetables are flexible, student-centred, and self-managed. |

| Students are able to express their voice. | Students are encouraged to express their voice by creating content through blogs, uploading videos to YouTube, and other digital tools and media. The experiences and views of students can reach a wide audience for feedback, including their peers, whānau, and the wider community. |

| Students can acquire the skills to select and use the appropriate technology and resources to support and enhance their learning. | Students can respond to tasks using a variety of digital tools. They can choose from a range of mediums – whatever suits their goals. For example, art students visit a gallery in order to document their favourite pieces, describe and evaluate them, and share their documentations with their peers. The students are encouraged to find a digital tool that can help them do this. It may be that they take photos of the exhibits, upload them to flickr , and use the site’s tools to tag, annotate, and comment on what they’ve seen. Or, they will create an Instagram group in which they can upload images and videos and comment on each other’s posts. |

| Students build a network of peers, teachers, and experts to guide and support their learning. | Students are encouraged to reach out to experts (both within and outside the school), industry professionals, and the wider community in order to assist with their learning goals. For example, students creating an online game modification contact a game designer for advice, expertise, coding tips, or involvement in their project. Watch Daniel Cowpertwait describe the Portal Unity project » |

| Students can demonstrate mastery of learning content. | Students can articulate and reflect on the what, how, and why of their learning. They can identify their strengths and what they need to work on. e-Portfolios and Learning Management Systems like Moodle can be instrumental in facilitating learner reflection. By showing learning progression over time, e-portfolios and LMS help students show evidence of having understood and taken control of their learning. |

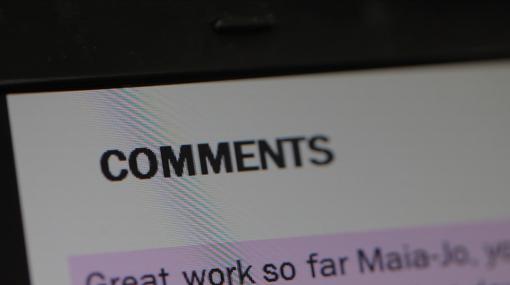

| Students become self-directed, experts of learning who monitor progress, provide self-directed assessment and reflect on learning. | Students can post work on a blog space or padlet and receive immediate feedback from peers by commenting on each other’s work. They can design their own assessment rubrics for projects. Google docs and other web 2.0 applications allow for collaboration, showcasing of work, and instantaneous feedback from teachers, parents, and Whānau. |

| Students have access to flexible, personalised learning environments. | Students have choice in where they work – they can find the space in the school that works best for them. Furniture is flexible, allowing students to arrange the classroom for both collaborative work and quiet time. Digital technologies can be used create different learning spaces, for example the "flipped classroom" allows students to access material anywhere anytime. Online tools enable collaboration and sharing, and online blogs provide a space for solitary reflection. In flexible spaces, learning pedagogy and design-theory meet to define a people-based, flexible learning environment. |

| Learning takes place through relevant, authentic, real-world contexts. | Projects can model real-world activities, solve real-world problems, and have real impacts on the school environment and lives of students. These projects can be multidisciplinary, and draw on the expertise of a wide range of teachers, local experts, peers, Whānau, and peers. For example, students can set up a school horticultural company. They take on defined roles, such as market researcher, business strategist, financial officer, web designer, agricultural scientist, builder, architect, graphic designer, and so on. They consult teachers and members of the local community to build the greenhouse, grow the vegetables, market the products, set up a stall at the school fair, and so on. Watch Woodend School students respond to issues in their local environment » |

In a personalised learning environment, students can use digital tools and technologies to learn at their own pace. They can access and revisit content to support them with achieving their learning goals. They can be the experts, share their learning, and provide feedback to their peers. They can showcase their expertise to a selected audience using the digital tools that work best for their need. Students can work at their own pace according to intrinsic motivations, leading to higher engagement, and improved student outcomes.

Kate Friedwald, teacher at Wairakei School, describes how students in her classroom use iPads to engage in independent, self-directed learning.

Key resources

Making Learning Personal

This site is maintained by personalised learning specialist Kathleen MacClaskey.

Personalising learning: Principal's Perspective

Pat Heargreaves research project includes the views of principals in schools around New Zealand on personalising learning.

Affirming cultures, languages, and identities

Plan learning that acknowledges who your students are and where they are from.

- Start with students' culturally-located needs and strengths.

- Create ongoing opportunities for students to share where they are from, what is important to them and why.

Susan Lee, Te Kura o Kutarere, shares how using Storybird , a free digital story writing tool, has made a significant impact on the literacy development of her students. She describes how students have become self motivated and proud of their work. Susan's planning is based on her learners. She designed the learning around who they are and where they are from, with literacy being grounded in local stories from Opotiki and the kura’s place-based curriculum. The student in the video clip makes these connections when he says, “It's about Māori people and dragons and stuff and yeah, it's Maui. He put on a meeting for all the people of Opotiki.”

This approach allows students to:

- bring their prior knowledge (ako)

- work reciprocally, learning by modelling, watching, and doing

The technology (Storybird on laptops) supports the local focus, the reciprocal nature of the activity, and the different strengths and needs of the students.

Teachers from Pegasus Bay School discuss how introducing waiata, students learning their pepeha and rakau games has created an inclusive environment where tikanga Māori is celebrated and valued.

Peer support

By creating classrooms that encourage peer supports, we:

- capitalise on the knowledge and abilities of our students and their relationships

- take the pressure off of ourselves to have to do and know everything all of the time.

Consider the following:

- individual student learning strengths and needs

- develop and explain roles and expectations in peer partnerships

- teach basic strategies for supporting support the academic and/or social participation of peer partners

- provide means for ongoing feedback and assistance to peer partnerships

- shift teachers' aides to a broader support role in which they assist all students in the classroom.

Students at Houghton Valley School made a book using digital photos with simple captions to help prepare a student needing extra support for their first school camp experience.

Matt is a Year 13 student at Wairarapa College. In this video Matt, who has low vision, describes how, with technology and the help of friends, he accesses and participates in the curriculum alongside his peers.

Key resource

Supporting positive peer relationships in the classroom

This guide focuses on supporting relationships between students to develop their sense of belonging and wellbeing and to improve their learning outcomes. It outlines whole-class and small group strategies that support every student to build relationships and work successfully with others.

Adopting an inclusive pedagogical approach

Employ an inclusive pedagogical approach that includes everybody rather than an individualised approach that focuses on "most" and "some" students.

Peer group collaborative learning

A comparison of what an inclusive pedagogical approach that includes all students looks like compared with an individualised approach in the classroom.

Shift the focus from those individuals who have been identified as having additional needs to the learning of all children in the classroom

- Create learning opportunities that are sufficiently made available for everyone, so that all students can participate in classroom life.

- Extend what is ordinarily available for all learners rather than using teaching strategies that are suitable for most alongside something additional or different for those who experience difficulties.

- Focus on what is being taught, and how, rather than who is to learn it.

Reject deterministic beliefs about ability as being fixed and the idea that the presence of some will hold back the progress of others

- Believe that all students will make progress, learn, and achieve.

- Focus teaching and learning on what students can do rather than what they can't.

- Use a variety of group strategies to support everyone's learning rather than relying on ability grouping rather than ability grouping to separate "able" and "less able".

- Use formative assessment to support learning.

See difficulties in learning as professional challenges for you, rather than deficits in the students

- Try out new ways of working to support the learning of all students.

- Work with experts and support staff, eg RTLB, teacher's aide to respect the dignity of all students.

- Seek ongoing professional learning to develop more inclusive practices.

Adapted from Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2010

Kate Friedwald teaches Years 5 and 6 at Wairakei School. In her classroom, groups are needs-based rather than ability-based. She and Daniel, a student with ADHD, talk about how this approach has helped him to be a successful learner. This type of grouping allows all students, Daniel included, to help each other. Daniel can use his skills with his app to help students that are even working a level above him in writing. Rather than always being in the bottom or top group, students work with others learning the same skill.

Key resource

Developing an inclusive classroom culture

An inclusive classroom is one that values the contributions of all students, their families/whānau, and communities. This guide, from the Inclusive Education website, includes strategies, suggestions and resources to encourage more student and whānau input in developing an inclusive classroom.

Using digital technologies to include parents and whānau in learning

"If the teacher demonstrates cultural knowledge it has an effect on the children. They see the teacher as an individual who respects them and knows where they are coming from. The children see those teachers who have made an attempt to try and get on the same thought patterns, wave-length as them."

– Māori parent, Te Kōtahitanga Phase 1:The experiences of Year 9 and 10 Māori students in mainstream classrooms

Consider how you will:

- make personal connections with parents and whānau?

- make language and invitations inclusive?

- approach and partner with parents and whānau to seek their perspectives and address their concerns?

- create opportunities to connect parents and whānau with students, other parents, and community leaders?

What kind of workshops, presentations, parent evenings can you plan? How will you organise these so parents and whānau are able to come, feel welcomed, and have their ideas and concerns listened to and addressed? How can you use digital technologies to support communication and collaboration?

Hillcrest Normal School teacher, Michelle Macintyre shares how technology has enabled parents to be involved in different ways with students' learning. She explains, at their classroom learning celebrations they have been engaging parents with technology in practical ways. Creating video of learning experiences facilitates discussion between students and parents, particularly for English as a second language families. The class blog has become a portal for parents to interact with. It's become an e-portfolio where student progress is shared.

Sharing learning

Communicate and share information in ways that work for everyone, for example: social media, email, a class blog, newsletters with photos, e-portfolios.

Parents from Holy Cross School explain how they are able to connect easily with the school, using mobile devices and different forms of electronic media such as the school website, Facebook, email, text, and Google docs. This anytime anywhere connection enables them to engage with and support their students learning.

Students at Motu School use e-portfolios for goal setting, sharing their learning, and reflecting on their progress. Students lead the three way conferences with parents and teachers, using the e-portfolios to share and explain their learning. This process means conversations about learning are more focused. Students value parent feedback and engagement in their learning. Having the portfolios online means parents can access and be part of their children's learning at anytime.

Miranda Makin (DP Albany Senior High School) explains the benefits of using e-portfolios for students participating in the Impact Projects . e-portfolios showcase the richness of the learning through images, video, and audio. The students' e-portfolios provide an online document for students to take with them when they leave school that demonstrates the kinds of competencies and skills they have developed.

More information »

Filter by: Primary Secondary Cultural responsiveness Diverse learners UDL

Sorry, no items found.

Resources

Key resource

Inclusive education: Guides for schools

This site provides New Zealand educators with practical strategies, suggestions and resources to support learners with diverse needs.

Inclusive classrooms project

Support for teachers striving to make their classrooms and their practices more inclusive. It contains some explanations of practices that can support inclusivity in schools, suggestions for further reading in specific topics of interest.

What an inclusive school looks like

This information sheet describes what an inclusive school looks and feels like in the English-medium context. Use the information to reflect upon and review the inclusive values, policies, and practices in your school.

Inclusive toolkit

The Inclusive Practices Tools explore the extent to which school practices are inclusive of all students

Success for all: Every school, every child

The Government has set a target of 100% of schools demonstrating inclusive practices and improving special education systems and support. The Success for All resources can be downloaded from the Ministry of Education website.

Inclusive practice in secondary schools: Ideas for school leaders

The purpose of this resource is to give secondary school leaders ideas for discussing inclusive practice in your schools. It is intended to start the discussion and help school leaders reflect on what is working well and what may need to improve.

Developing learner profiles

A learner profile tells teachers about students. It sits alongside assessment data. It helps school staff to build relationships with students and to understand things from a student perspective. This can inform planning, classroom layout, and supports to enable students to participate and contribute in all classroom learning.

Relationships and Sexuality Education: A Guide for Teachers, Leaders, and Boards of Trustees

This refreshed resource focuses strongly on consensual, healthy and respectful relationships as being essential to student wellbeing. It is available in two volumes: one for years 1–8, and one for years 9–13.

The guide informs principals, boards and teachers on the requirements of the Education and Training Act 2020. It also assists schools to consult with their community on the ways in which health education should be implemented.

Safety in our schools Ko te Haumaru i o Tatou Kura

An action kit for Aotearoa New Zealand schools to address sexual orientation prejudice. Safety in our schools ~ Ko te haumaru i o tatou kura presents information and strategies to assist Boards of Trustees (BOTs), principals and staff to develop environments for their school communities that are inclusive of sexuality and gender diversity.

The New Zealand Curriculum principle of inclusion. Information and links to tools, examples, and resources.

Inclusive practice and the school curriculum

Inclusive Practice and the School Curriculum is a resource for teachers and leaders in New Zealand English-medium school settings. It has been developed to build professional knowledge and create a shared understanding of inclusive practice within The New Zealand Curriculum.

Research

Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES)

This best evidence synthesis has produced ten characteristics of quality teaching. The central professional challenge for teachers is to manage simultaneously the complexity of learning needs of diverse students.

School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why best evidence synthesis iteration (BES)

This BES provides examples of principals and others in leadership activities that advance achievement and social outcomes for students. The theory included in the synthesis explains how and why is critical to enable leaders to adapt and use the findings in their own contexts.

The New Zealand Curriculum principles: Foundations for curriculum decision-making

This is ERO’s second national evaluation report looking at the extent to which the principles of The New Zealand Curriculum are evident in schools’ curricula and enacted in classrooms. The curriculum principles are intended to be the basis of curriculum decision-making at schools. The findings in this report show that there is considerable variability across schools in the level of evidence of the curriculum principles.

Te Kōtahitanga phase 1:The experiences of Year 9 and 10 Māori students in mainstream classrooms

Researchers talked with Māori students, who clearly identified the main influences on their achievement. They said that teachers, in changing how they related and interacted with Māori students in their classrooms, could help students succeed.

Inclusive practices for students with special education needs in schools (March 2015)

This ERO report examines how well students with special education needs are included in New Zealand schools. The report provides an update on progress towards meeting the Government target that, by the end of 2014, 80 percent of New Zealand schools will be doing a good job and none should be doing a poor job of including and supporting students with disabilities.

Ki te Aotūroa: Improving inservice teacher educator learning and practice

A literature review to help in service teachers learn more about inclusion in NZ classrooms.

Literature review on the experiences of Pasifika learners in the classroom

This literature review examines the current practices of schools, teachers, and the wider education system in relation to Pasifika achievement, as well as outlining the proven pedagogical methods that facilitate inclusion and lift success.

Wellbeing for young people's success at secondary school (February 2015)

This report presents the findings of ERO’s evaluation of how well 68 secondary schools in Term 1 2014 promoted and responded to student wellbeing.

Inclusion: Cultural capital of diversity or deficit of disability? Language for change - Timoti Harris – Sabbatical report 2014

If we do not change our language to match changes in thinking, we perpetuate what always was. If we keep talking about “special education, disability, dysfunction, disorder”, we focus on the deficit. We have changed theory, we have changed practice, but we haven’t changed the language. Timoti Harris reports on creating an environment truly inclusive of ability, ethnicity, culture, gender and language at Otorohanga College.

Leadership in the development of inclusive school communities

Dr Jude McArthur gives an overview of the research she and others have undertaken in the schooling sector about the experiences of young people who have disabilities. She connects the key themes to what school leaders can do to support developing their schools as inclusive communities. Learning better together: Working towards inclusive education in New Zealand schools

is Dr McArthur’s research into inclusive education in a New Zealand context.

The gifted child and the inclusive classroom

Rosemary Cathcart presents two decades of research on ability grouping. She looks at arguments both for and against grouping, and at various forms of grouping, poses some crucial questions for policy-makers, offers a re-definition of 'inclusive', and suggests an approach relevant for Aotearoa/New Zealand.