Using digital technologies to support culturally responsive leadership

What is culturally responsive leadership?

Culturally responsive leadership supports inclusive environments and improved learning for students and families with culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. It involves developing leadership pedagogies, practices, and policies that create inclusive schooling environments.

Culturally responsive leadership is an individual and a collective responsibility

Culturally responsive leaders:

- exhibit an ethic of care

- develop cultural awareness in the school and community

- demonstrate and promote inclusive practice

- challenge deficit theorising, inequitable principles and practices.

Regardless of position or age, any member of the staff and any student has the ability to be a culturally responsive leader.

A bi-cultural approach to culturally responsive leadership

Lead for diversity

To lead for diversity means to actively respond to the diversity in the school population. Educational policy and practice reflecting a Māori worldview as legitimate, authoritative, and valid has the potential of creating a culturally responsive approach that benefits the entire school community.

The New Zealand Curriculum acknowledges the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the bicultural foundations of Aotearoa New Zealand. All students have the opportunity to acquire knowledge of te reo Māori me ōna tikanga.

The Treaty principle of partnership benefits all learners. It harnesses the knowledge and expertise of the diverse people who can contribute to students’ learning, including families, whānau, iwi, and other community members.

How do schools honour Te Titiri o Waitangi?

As Treaty partners, schools honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi by giving mana to each of the four treaty articles:

Article 1: Kāwanatanga – Honourable Governance (recognition of sovereign power that no one has rights over other groups of people including tangata whenua)

Article 2: Rangatiratanga – Recognises that Māori have a right to self-determination, authority and agency

Article 3: Ōritetanga – Equity (Māori have the right to maintain their own rights)

Article 4: The spoken promise – Spiritual beliefs and practices will be protected for both Pākehā and Māori.

Giving mana to Tiriti o Waitangi in our schools

In this video, Janelle Riki-Waaka discusses how focusing on what it means to be a school unique to Aotearoa New Zealand and reflecting our bicultural heritage gives mana to Tiriti o Waitangi. Janelle encourages educators to ask themselves: How would I know I am in a school in Aotearoa? She believes it is a moral and ethical imperative to protect and honour te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and our bicultural history for every student in every school in New Zealand.

Looking at the Treaty of Waitangi curriculum principle

In this video, Wharehoka Wano offers schools simple strategies to get started and describes what might be seen in classrooms where the Treaty of Waitangi principle is enacted.

Whare comments on the importance of school leaders and kaiako knowing:

- their community – including their Māori community

- where their tamariki Māori come from and the relationship they have with that place.

Schools should know what tribal area they’re located in, and the rivers and mountains that are important.

Key resources

This document outlines roles and focus areas of leadership from a Māori perspective and presents some of the key leadership roles and practices that contribute to high-quality educational outcomes for Māori learners. Initially created for Māori medium educational leadership, this is a useful resource for all school leaders.

Māori achieving success as Māori (MASAM)

A framework for developing a school curriculum that supports Māori students to enjoy and achieve educational success as Māori.

Cultural responsiveness sabbatical report (2020)

Chris Meynall gathered information about how cultural relationships are reflected in the pedagogy and curriculum of NZ schools in Hawkes Bay, Wellington and Bay of Plenty.

Principal, Roger Hornblow describes their two-and-a-half-year journey to build culturally inclusive practices at Pegasus Bay School. They began by involving whānau and the community to develop their place-based approach to learning. Consultation with the Ngāi Tūāhuriri Education Committee (Ngāi Tahu) was ongoing from the early stages of designing the new school.

Place-based learning can help teachers practise a culturally responsive pedagogy which is grounded in the unique historical, cultural, and ecological contexts their students live and learn in.

Each of the learning communities at Pegasus Bay School incorporates local names and stories, which are part of students' learning. Roger describes two whole-school PLD projects undertaken by staff to build their understanding of Māori tikanga and reo. They have made te reo Māori and inclusive approaches part of their everyday practice so they are seen as "business as usual" by students and parents.

Online PLD – Te Reo Puāwai

Online professional learning was made available for the whole staff through the Te Reo Puāwai course – a guide to te reo Māori, which includes how to teach it to others and use it authentically in your setting. The value of working online meant teachers could work at their own pace, revisit the lessons and resources, and work together to build understanding and develop practice.

Huakina Mai

Pegasus Bay School trialed Huakina Mai trial, along with two other schools in their area. Huakina Mai aims to enhance learning outcomes and experiences for Māori students and their whānau by supporting schools, students, whānau, and iwi to build a whole school approach to positive behaviour based on strong relationships, authentic engagement, power sharing, culturally responsive behaviour management systems, processes, practices and pedagogy (ways of teaching and learning). Roger notes the importance of connecting with the two other schools in the trial.

Strategies that can lead to change

Create effective links between school and other cultural contexts in which students are socialised, to facilitate learning. Use a blended approach, which includes face-to-face and online.

- Prioritise the importance and facilitation of face-to-face relationships between school staff and students, whānau, and other community members.

- Establish systems and structures to support the development of relationships – support whānau to view student work online and engage in their learning.

- Create a culture of learning within the entire school community – invite whānau into the school and connect with local marae.

(Ford, 2012 )

School examples

Teachers from Pegasus Bay School discuss how students learning their pepeha, rakau games, waiata, and karakia has created a culturally responsive environment where tikanga Māori is celebrated and valued. Teachers work hard to connect with whānau. Student work is shared through classroom blogs. Teachers have organised workshops using parent and whānau expertise with harakeke weaving leading up to Matariki. Feedback from whānau has been positive.

Te ika unahi nui wānanga – A marae-based learning programme

Students from Coastal Taranaki School learn at Tarawainuku marae. The marae holds the cultural knowledge of the local tribe inside its houses and in the environment in which it is located. Whānau were invited to provide their input into designing learning experiences and encouraged to participate in these at the marae each week with the students. Regular meetings were held to discuss learning for each term.

Rob Clarke, principal of Burnham School, explains the importance of face-to-face meetings in terms of successful whānau and community engagement with e-learning tools.

Face-to-face dialogue and relationship building helps to eliminate “guesswork” when identifying possible barriers and opportunities for student and teacher learning. Provide opportunities for the leadership team and teachers to have conversations with, and listen to, Māori students, whānau and the wider Māori community to gain a deep understanding of where students are from and what they bring into the school setting. Find out about the expectations and aspirations that parents have for their children.

As well as ensuring that leaders and teachers are building interdependent relationships with students, parents and community members, and the principal, consider the quality of internal relationships between leaders, teachers, and administration staff. Provide staff with opportunities to share their ideas and perspectives, so they are empowered to contribute to decision-making.

Develop a shared vision

Use understandings gained from conversations with Māori students, parents and whānau, fellow leaders, teachers, and support staff to guide the development of a shared vision. Develop a vision that ensures all students (particularly those being least served in the school in terms of education success) are better able to achieve academic success. Use your vision to inform school systems and structures.

Key resources

Leading schools that include all learners

This online guide unpacks what it means to lead an inclusive school where all students are supported to be present, engaged, participating, and achieving in ways that honour and value diversity.

This toolkit is designed to highlight the opportunities and outline the challenges specific to greater use of technology in the service of diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. It is designed for organizational leaders, Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officers (CDIOs), and others actively working to promote diverse, equitable and inclusive workplaces globally.

Kawa and tikanga – systems and structures

Design systems and structures that articulate "how your school does things" to create an inclusive culture that supports learning.

- Provide multiple opportunities for engagement with school families, particularly Māori whānau.

- Plan and timetable regular parental meetings, information evenings, and events to celebrate learning into the school schedule each term.

- Encourage teachers to target parent drop-off and pickup times for informal opportunities to talk with parents about their children.

- Plan regular meetings between the senior leadership team, teachers, and administration staff to ensure shared understandings about how staff relate to and interact with students, parents and one another. These meetings also provide opportunities for staff to have their voices heard and professional needs responded to in an individual and collective way.

Regularly review and update documents to reflect developing understandings of culturally responsive practice, as a result of ongoing dialogue with students and parents, and through your professional development programme.

Cultural responsiveness needs to permeate every aspect of the school to create an inclusive environment, including the:

- physical environment

- policy and procedures

- curriculum

- relationships among teachers, students, and the community (Williams, 2016 ).

Key resources

A series of videos on the NZC website supporting understanding and leading whole school te reo Māori development, effective pedagogy, and a culturally connected curriculum.

Partnering with parents, whānau, and communities

This online guide provides information, examples, and resources to support schools to develop and strengthen effective partnerships. It emphasises the value of building close community networks to support student learning and wellbeing.

Policies

ERO suggest schools can improve their practice by building their understanding of the Treaty of Waitangi and its implications for school policy, organisation, and planning (Ministry of Education, 2012 ). Consider to what extent the Treaty of Waitangi principle is evident in the interpretation and implementation of your school curriculum and how it is enacted in classrooms.

Use important policies that guide the school as a basis to develop practice guidelines, in conjunction with teachers, which contain expectations regarding relationships and the classroom.

Consider your:

- curriculum delivery policy

- Treaty of Waitangi policy

- appraisal and attestation policy

- school charter and strategic plan.

"To ensure that all Māori can achieve their full potential in education, the system must fit the learner rather than the learner fit the system."

Ministry of Education, Supporting Māori students

Establish and support pedagogies and frameworks that underpin culturally responsive practices by:

- emphasising high expectations for student achievement

- incorporating the history, values, and cultural knowledge of students and community in the curriculum

- developing organisational structures that reflect the cultural diversity in the school and wider community

- providing relevant learning opportunities to improve educational experiences and outcomes for all students

- building relationships between schools and communities.

Key resource

The Treaty of Waitangi and school governance: Ki tua tua o te matapaki kōrero ko te mahi

This document enables trustees of English-medium schools to better understand the Treaty; emphasise the responsibility and potential that boards have in ensuring that the implications, obligations and the spirit of the Treaty are implemented and upheld.

Localised curriculum – bicultural by design

"Your local curriculum is the way that you bring The New Zealand Curriculum to life at your school. It should: be responsive to the needs, identity, language, culture, interests, strengths and aspirations of your learners and their families. have a clear focus on what supports the progress of all learners."

Ministry of Education, Local curriculum: Designing rich opportunities and coherent pathways for all learners

Student-centred schools will put their students, their whānau, hāpu and iwi at the centre of learning design and will honour those voices in shared decision-making processes.

Systems will create honourable and respectful communications and programmes of learning that reflect our dual heritage in Aotearoa (past, present and future).

Māori tikanga and kawa, appropriate to local contexts, will also value and prioritise te reo, tikanga and mātauranga Māori and respect spiritual beliefs and practices of both Māori and non-Māori.

Effective pedagogy will remove educational barriers and inequalities are removed to ensure equitable educational outcomes by valuing Māori diversity, giving Māori agency, voice and choice resulting in outcomes where Māori achieve success as Māori.

School examples

Local histories – a student’s perspective

Arapeta Latus, a senior student at Whanganui City College, talks about the importance of hearing local history from local people and visiting sites of significance where possible. Video source: Hītori Māori –Maori history

Map my Waahi

"Social mapping is the term given when technologies are used to aggregate geospatial information and blend it with local knowledge about people, places, events, and features...bringing our local stories and cultural histories to life in authentic and meaningful, valid and reliable ways. This is where multiple voices and their perspectives can be heard, enriching local and contextualised knowledge."

CORE Ten Trends 2019, Social mapping

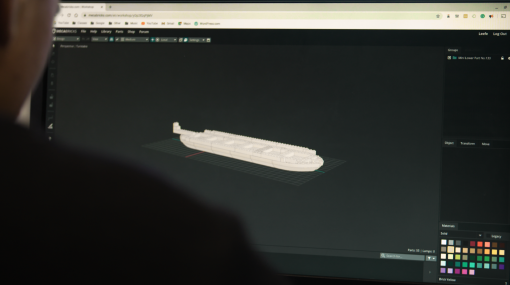

The LEARNZ virtual field trip Map my Waahi connects students to their cultural and physical landscape:

Use mapping technology like Google Earth and Google My Maps to create personalised, culturally located learning activities.

Connecting with your community

Connection between the school and the community is essential in developing school-wide culturally responsive practices.

Research indicates that when schools develop educationally powerful connections with whānau and their Māori communities there is potential to significantly improve learning outcomes for Māori students (Berryman, Ford & Egan, 2015, p. 18 ).

Both partnership and collaboration infer a degree of power-sharing. Consider what power-sharing means in terms of engagement with Māori whānau and communities. A productive partnership is described as being a two-way, mutually respectful relationship that “starts with the understanding that Māori children and students are connected to whānau and should not be viewed or treated as separate, isolated or disconnected” (Ka Hikitia Accelerating Success 2013 - 2017, p. 18 ).

Understand and be responsive to the cultural conditions of your particular school community by:

-

interacting with the students and their families to truly understand their reality

- understanding families' cultures and they it impact classroom life

- challenging personal beliefs and actions

- changing practices to engage all students in their learning and make the classroom a positive learning place for all students (Earl, Timperly & Stewart, 2008) .

Using digital technologies to support partnerships

Identify how you can use digital technologies to support and facilitate your partnerships. This may mean providing parents and whānau with support to access and use the technologies.

Holy Cross School is a multicultural community. Kathy Moy-Low explains how they engaged with their community while building e-learning opportunities. One of their initiatives is after-school parent technology sessions, which run once a month. In this video clip, parents explain why they go to the classes – the benefits for their own learning with technology, and how they can engage more with their children's learning.

More information »

- Māori achieving success as Māori

- A marae-based learning programme

- The Mutukaroa project

- Connecting with Pasifika families and communities

Embracing cultural narratives

"A cultural narrative describes what is unique about the place and the people your educational setting is part of. In the New Zealand context, a cultural narrative recognises the histories of and by mana whenua (tribes who have territorial authority over land), their sacred places, their interactions with the land and their ways of being as a people. It helps build a common understanding of their values, their heritage and their traditional and spiritual connections to the land and the environment.

The Cultural Narratives of mana whenua embody the essence of who they are. It supports authentic engagement with whānau, hapū and iwi because it invites all these groups to not only contribute their stories, and invites them to be able to participate as mana whenua on their lands their tamariki are educated on."

– CORE Ten Trends 2019, Cultural narratives

"A local cultural narrative may contain a range of things that mana whenua would like your school to understand, share and embrace. This could include:

- whakapapa

- significant sites, landmarks and geographical features

- historical events

- relationships with flora and fauna

- local language

- local stories, waiata, whakataukī, symbols."

– Educational Leaders, Cultural narratives

Cultural narratives and Earth Education at Ngunguru School

Video source: EDTalks: Cultural narratives and Earth Education at Ngunguru School

Cultural narratives are entwined with science and environmental studies in Earth Education at Ngunguru School. The EarthEd programme aims to embed the role as protectors of the environment (kaitiakitanga) into students' everyday life, and is more than just educating about the environment. Through this school-wide programme students develop meaningful and authentic connections with the local environment and local history, and with the earth.

More information »

- Technologies suitable for different types of communication for more information on ways to use e-learning to connect with whānau and the wider community

Akoranga – Creating a culture of learning

Providing professional learning and development (PLD) for staff is an important aspect of influencing cultural responsiveness. To support staff to successfully develop culturally responsive practices, leaders need to know:

- the complexity and stages of each staff member's journey toward developing cultural responsiveness

- the different cultural experiences and beliefs they hold (Williams, 2016 ).

Support staff to:

- increase their understanding of their own culture and the influence it has on their teaching

- gain some understanding of how Pākehā culture influences education and develop an appreciation of the effect this has on children from ethnic minority groups

- increase their knowledge of the cultural background of the learners they teach and use this information to provide effective learning for these groups of children (Patara, 2012 ).

At Pegasus Bay School, teachers teach and use te reo Māori daily so students hear and see it as a natural part of their school culture. Pegasus Bay School principal, Roger Hornblow explains the importance of being deliberate about giving teachers skills at a personal level, which have practice and performance outcomes. Working through the online course, Te Reo Puawai, together as a whole staff meant teachers could collaborate, support each other, and develop their practice together.

Teachers are aware of the importance of using te reo Māori regularly and pronouncing it correctly. Students and teachers are learning together. Kupu and posters placed around the learning environment provide te reo support.

Tamariki are encouraged to bring things in which are meaningful to them. They have gathered things such as shells, toi toi, and harakeke, from their local environment which are used as classroom resources.

Understanding the aims of culturally responsive practice

"The aim of culturally responsive teaching and learning is to improve Māori education outcomes where the tamaiti (child), the whānau (parents and family), and hapū and iwi (tribal group) are integral to determining the education journey. The core of cultural responsiveness is: responding to 'the child’s cultural experiences' – in this case as Māori and all that it encompasses."

Understanding diversity

Diversity encompasses many characteristics including:

- ethnicity

- socio-economic background

- home language

- gender

- special needs

- disability

- giftedness.

Teaching needs to be responsive to diversity within ethnic groups, for example, diversity within Pakeha, Māori, Pasifika and Asian students. The diversity among individual students influenced by intersections of gender, cultural heritage(s), socioeconomic background, and talent also needs to be recognised. Evidence shows teaching that is responsive to student diversity can have very positive impacts on low and high achievers at the same time (Alton-Lee, 2003 )

Effective practice

Plan learning that acknowledges who your students are and where they are from.

- Start with students' culturally-located needs and strengths.

- Create ongoing opportunities for students to share where they are from, what is important to them and why.

Characteristics of culturally inclusive practice

These characteristics are interdependent.

- Teachers ensure that student experiences of instruction have known relationships to other cultural contexts in which the students have been/are socialised.

- Relevance subject material is made transparent to students.

- Cultural practices at school are made transparent and taught.

- Ways of taking meaning from text, discourse, numbers, or experience are made explicit.

- Quality teaching recognises and builds on students' prior experiences and knowledge.

- New information is linked to student experiences.

- Student diversity is utilised effectively as a pedagogical resource.

- Quality teaching respects and affirms cultural identity (including gender identity) and optimises educational opportunities.

- Quality teaching effects are maximised when supported by effective school-home partnership practices focused on student learning. School-home partnerships that have shown the most positive impacts on student outcomes have student learning as their focus.

- When educators enable quality alignments in practices between teachers and parents/caregivers to support learning and skill development then student achievement can be optimised.

- Teachers can take agency in encouraging, scaffolding and enabling student-parent/caregiver dialogue around school learning.

- Quality homework can have particularly positive impacts on student learning. The effectiveness of the homework is particularly dependent upon the teacher's ability to construct, resource, scaffold and provide feedback upon appropriate homework tasks that support in-class learning for diverse students and do not unnecessarily fatigue and frustrate students.

Identifying effective practice

Culturally responsive teachers use a wide variety of strategies to create inclusive classroom contexts where students are encouraged to acknowledge and celebrate diversity and learn with and from each other. These include:

Quality relationships are central to quality teaching

- building care-based relationships that underly all classroom interactions

- power sharing between students and teachers

- challenging deficit theories of achievement

- making students’ cultural and ethnic identities and knowledge fundamental dimensions to curriculum design (Gay, 2000; Wlodkowski & Ginsberg, 1995 in Ford, 2010 ).

The Effective Teacher Profile (ETP) illustrates effective interactions:

- manaakitanga (caring for students as Māori and acknowledging their mana)

- mana motuhake (having high expectations)

- ngā whakapiringatanga (managing the classroom to promote learning)

- wānanga and ako (using a range of dynamic, interactive teaching styles)

- kotahitanga (teachers and students reflecting together on student achievement in order to move forward collaboratively).

Tātaiako – cultural competencies for teachers of Māori learners

- ako (teachers taking responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners)

- wānanga (robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement)

- manaakitanga (valuing Māori beliefs, language and culture, caring for students as Māori and acknowledging their mana)

- whanaungatanga (actively engages in respectful working relationships—tamaiti/whānau/hapū/iwi)

- tangata whenuatanga (affirms Māori learners as Māori).

Culturally responsive teaching and learning pedagogy is realised when:

- teachers’ cultural competence increases

- teachers’ deficit theorising is reduced

- teachers build positive relationships with students

- teachers have high expectations of Māori learners

- Māori learners bring their cultural experiences into the classroom to inform learning and teaching (mana motuhake)

- Māori learners and extended whānau are integral to determining Māori education success.

Tau Mai Te Reo and Ka Hikitia are companion strategies and should be read in conjunction with each other. Tau Mai Te Reo is a strategy for all learners, while Ka Hikitia is a strategy for all Māori learners.

- Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaitia | The Māori Education Strategy

- Tau Mai Te Reo | The Māori Language in Education Strategy

Tapasā – Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners

Increase the capability of all teachers of Pacific learners.

- Tapasā resources – video resources with conversation starters and supplementary resources.

- Quality Practice Template – Cross Sector Examples for a QPT using a Tapasā lens – a description of quality practices and evidence teachers can gather to demonstrate competence in each Teacher Standard.

Supporting teachers develop culturally responsive practice using digital technologies

"Culturally responsive teaching is about making school learning relevant and effective for learners by drawing on students’ cultural knowledge, life experiences, frames of reference, languages, and performance and communication styles.

Culturally responsive teaching recognises and deeply values the richness of the cultural knowledge and skills that students bring to the classroom as a resource for developing multiple perspectives and ways of knowing. Teachers communicate, validate and collaborate with students to build new learning from students’ specific knowledge and experience.

Culturally responsive pedagogies can reduce the gaps between the highest and lowest achievers while at the same time raising overall levels of achievement. Culturally responsive pedagogies raise student achievement for all cultural groups, ensuring that all students are given the encouragement and support to realise their educational potential regardless of their social, economic or cultural background or individual needs.

While student diversity is increasing, there is a general lack of diversity amongst New Zealand’s teachers. Cultural gaps between students and teachers, when left unaddressed, can lead to misunderstandings of teacher expectations on the part of the student, or of student behaviour on the part of the teacher."

The Education Hub, Culturally responsive pedagogy

Teachers at Pegasus Bay completed an online course, Te Reo Puawai, over a term with ongoing access to the course content and resources for the year. They collaborated to plan learning and to build a culturally responsive environment. In these videos, teachers share the variety of strategies and approaches they developed to engage the tamariki with what is happening in their learning community. They explain the different technologies they use as part of their classroom programme to support learning and engage with parents and whānau.

Students use a variety of apps to create content, practice their reo, hear themselves, reflect on their learning with peers, and set goals for improvement. Content is shared with whānau through classroom blogs.

Te reo Māori is taught and used daily in the classrooms. Teachers agreed to plan 15-minute instructional lessons to make it manageable. They also include daily karakia, music, and games and identify features of their learning environment that reflect the culture of their learners and provide prompts to support using te reo Māori.

Digital Resource – Using digital tools for inclusive practice

More information »

- Teacher standards and e-learning – This page contains details on Standard 1: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership as well as Tātaiako and Tapasā competency frameworks. School leaders can use it to support teachers to develop and grow culturally responsive practices as they develop their use of digital technologies for learning.

- Supporting place-based education with digital technologies – By focusing on local stories, Place-based education can show how past events have shaped a student's own life and surroundings.

- Digital tools supporting te reo Māori – A collection of online resources to support learning and teaching using digital technologies.

- Supporting Māori learners – Information, resources, and examples of classroom practices to provide an environment that supports Māori to achieve as Māori.

Go to the School stories tab for more examples of using digital technologies in the classroom.

Sorry, no items found.

Publications and initiatives

The Treaty of Waitangi and school governance: Ki tua tua o te matapaki kōrero ko te mahi

This document enables trustees of English-medium schools to better understand the Treaty; it emphasises the responsibility and potential that boards have in ensuring that the implications, obligations and the spirit of the Treaty are implemented and upheld.

The cultural self-review: Providing culturally effective, inclusive education for Māori learners

This book by Jill Bevan-Brown provides a structure and process that teachers from early childhood centres through to secondary schools can use to explore how well they cater for Māori learners, including those with special needs. Central to the book is a cultural input framework that provides a set of principles for analysing programme components including environment, personnel, policy, processes, content, resources, assessment, and administration.

The pedagogies and practices supported by a bi-cultural and culturally responsive approach to leading teaching and learning will benefit the entire school community. Two examples of school leaders who have achieved better results for their Māori learners are outlined in the following New Zealand university master's degree theses’:

- Examining culturally responsive leadership (2010)

Culturally responsive leadership in Aotearoa New Zealand secondary schools (2016)

The New Zealand Curriculum Treaty of Waitangi principle

NZC Update 16 focuses on The New Zealand Curriculum principle the Treaty of Waitangi and its implications for teaching, learning, and the school curriculum.

Tātaiako: Cultural competencies for teachers of Māori learners

Tātaiako provides a framework that can support professional development and learning for teachers, leaders, and aspiring principals. The framework identifies five competencies and for each provides indicators at four levels: entry to initial teacher education, graduating teachers, certified teachers, and leaders. Supporting the indicators are possible outcomes expressed as examples of learner voice and of whānau voice.

Ka Hikitia – Kā Hapaitia is a cross-agency strategy for the education sector. It sets out how The Ministry of Education will work with education services to achieve system shifts in education and support Māori learners and their whānau, hapū and iwi to achieve excellent and equitable outcomes and provides an organising framework for actions.

Māori History in the NZ Curriculum

TKI site includes background information about why teach Māori history, programme design, contexts, and videos.

Tapasā – Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners

A tool that can be used to increase the capability of all teachers of Pacific learners.

- Tapasā resources : video resources with conversation starters and supplementary resources.

- Quality Practice Template – Cross Sector Examples for a QPT using a Tapasā lens : a description of quality practices and evidence teachers can gather to demonstrate competence in each Teacher Standard.

Action Plan for Pacific Education

The Action Plan maps the Government’s commitment to transforming outcomes for Pacific learners and families and signals how early learning services, schools, and tertiary providers can achieve change for Pacific learners and their families. The Action Plan has resources and guidance including planning templates.

Huakina Mai is a kaupapa Māori behaviour initiative that promotes whānau, schools, and iwi working together to build a positive school culture, based on a Kaupapa Māori world view. This initiative is based on the growing body of practice-based evidence that school and student/whānau success are improved by personalisation and strong relationships of teachers' knowledge of, and caring for students.

Ensuring culturally responsive practice

This page summarises some thinking and research related to building culturally responsive practice in your school.

Websites

Te Mangōroa is a portal to stories, reports, statistics, and reviews from across TKI and other sites that reflect effective practices to support Māori learners to achieve educational success as Māori. Te Mangōroa contains practical illustrations of what the Māori education strategy, Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaitia, means for teaching and learning.

- Effective leaders – this search result from Te Mangōroa provide a large number of research and readings to support school leaders develop a culturally responsive environment.

Inclusive education – Guides for schools

This site provides New Zealand educators with practical strategies, suggestions, and resources to support learners with diverse needs. Specific guides which may be useful:

Promise of place: Enriching lives through place-based education

Place-based education (PBE) immerses students in local heritage, cultures, landscapes, opportunities and experiences, using these as a foundation for the learning across the curriculum. PBE emphasises learning through participation in service projects for the local school and/or community. This American website provides useful information, templates for planning, and school stories to support understanding and implementing PBE.

Videos

A series of videos on the NZC website supporting understanding and leading whole school te reo Māori development, effective pedagogy, and a culturally connected curriculum.

Culturally responsive practice

A collection of videos featuring educators talking about culturally responsive practice, pedagogy, and learning environments.

Enabling e-Learning resources

Māori achieving success as Māori

A framework for schools to build an environment that supports Māori students to achieve success as Māori. School stories, information, and examples on how to develop a framework for your school.

A marae-based learning programme

Te Ika Unahi Nui is a marae-based wānanga (learning programme) that was developed and trialled with students from Coastal Taranaki School at Puniho Pā, Tarawainuku marae in Okato, Taranaki.

Mutukaroa is a home-school learning partnership that seeks to accelerate learning progress and achievement for students in years 1-3 by fostering the active engagement of parents and whānau in learning partnerships.

Connecting with Pasifika families and communities

Information and examples of how schools use digital technologies to support connections with Pasifika parents and families.

Information and examples of how schools use digital technologies to support the inclusion of all students. See also:

References

Berryman, M., Ford, T., & Egan, M. (2015). Developing collaborative connections between schools and Māori communities. Set 3

Earl, L.M., Timperly, H. & Stewart, G.M. (2008) . Learning from the quality teaching research and development programme (QTR&D): Findings of the external evaluation

Ford, T. (2012). Culturally responsive leadership: How one principal in an urban primary school responded successfully to Māori student achievement. Set 2

Harcourt, M. (2015). Towards a culturally responsive and place-conscious theory of history teaching. Set 2

Patara, L. (2012). Integrating culturally responsive teaching and learning pedagogy in line with Ka Hikitia. Set 2