Spiral of inquiry – Developing a Makerspace to create successful learning experiences for priority learners

Tags: Project based learning | STEM/STEAM | Teacher inquiry | Collaborative tools | Primary |

The year 7 and 8 teaching team at Marshland School establish a makerspace to increase engagement and enable successful learning for priority learners.

The Toroa teaching team worked collaboratively using Kaser and Halbert’s (2014) Spirals of Inquiry as a framework for their inquiry.

They investigated the effect of authentic learning on increasing student motivation and engagement. Students identified their own real-life problems in this project-based approach, and created solutions to these within the Makerspace the team developed. Students shared their products and learning at a Maker Faire where the local community was invited.

What are makerspaces?

Makerspaces are collaborative workshops where young people gain practical hands-on experience with new technologies and innovative processes to design and build projects. They provide a flexible environment where learning is made physical by applying science, technology, math, and creativity to solve problems and build things.

More information »

Scanning

“In Toroa, we noticed that not all students were motivated. It seems though, that when they are learning something they are interested in, or passionate about, often outside of school, they are quite different learners."

– Carolyn Davies, Toroa team leader

Focusing the inquiry

The team placed learners at the centre of their inquiry. They focused on knowing their learners – their abilities, interests both inside and outside of the classroom, and barriers to learning.

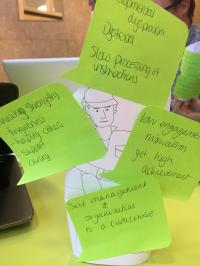

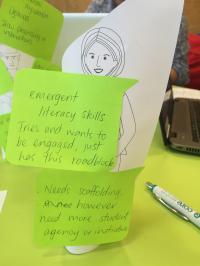

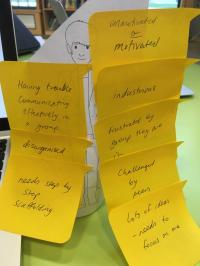

Developing learner profiles

Teachers built learner profiles and brainstormed the underlying factors behind their students' motivational challenges.

|

|

|

|

"We realised that these students have the ability, but not necessarily the drive, in class, and so we need to tap into different ways of teaching and learning for them.”

– Toroa teaching team

The team discovered that they had examples of learners who:

- spent hours absorbed in creating sophisticated and programmable LEGO technic vehicles – but quickly lost interest in class

- were mixed martial arts champions with drive and discipline within the dojo – but struggled to focus on school work for more than 10 minutes

- practiced the same piece of music over and over to get it just right – yet finished classwork as quickly as possible, not interested in working it over to achieve mastery.

Developing a hunch

Reflecting on teacher practice

“It may just be that the way they are being taught is not the way they think."

– Toroa teaching team

Teachers reflected on their practice and challenged their assumptions asking:

- What are the barriers to learning for our priority students?

- What teaching practises are contributing to these barriers?

- What strategies are successful?

- What are the consequences of our teaching practises?

- What do we need to do more of? What do we need to do less of? What is missing?

- Whose voice have we not heard?

- What do we need to learn more about?

After gathering and analysing student and whānau voice, alongside achievement data, and learner profiles, the team focused their collaborative inquiry.

Inquiry question

“How can we successfully integrate multiple disciplines and 21st century learning skills to engage, motivate, and develop different ways for our priority students to be successful?”

Learning

Teachers investigated the effect of authentic learning on increasing motivation and engagement among their students.

Reflecting on current research and past experiences, teachers identified factors that contribute to student engagement and successful learning.

The Maker Movement - or project-based learning - supports students to learn by doing (Martinez & Stager, 2016 ).

A past example of authentic learning

Students appreciated the skills, strategies, and experiences of soldiers by digging their own trench, as part of a study on World War. This rich learning experience made learning visible and deepened learning connections for both the students and the wider community.

This previous experience showed authentic learning engaged students and created memories that remained after they left primary school.

Identified factors that contribute to student engagement

- Authentic learning

- Hands-on, experiential, safe-to-fail learning opportunities

- Team building and learning about themselves as learners

- Joy – emotions are central to learning

- Increased connections between their learning, whānau, and the wider community.

Establishing a makerspace to facilitate collaboration and authentic projects

The Toroa team decided to use their makerspace to engage students who "get lost" in the traditional classroom and support student agency.

In the makerspace students can:

- tinker and take responsibility for their learning

- ideate, test, make mistakes, and learn in a safe-to-fail environment

- learn about themselves as learners and develop effective team skills

- create and collaborate on authentic tasks

- find joy in prototyping and making something of quality to share with whānau and community in a maker faire and market day.

Taking action: Scaffolding agency, 21st-century learning, and authenticity through makerspace

Principles underpinning the Taking Action phase of the inquiry

Kaupapa Māori principles:

- whanaungatanga – actively engaging in respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents, whānau, hapu, iwi, and the Māori community

- ako – taking responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners

- tuakana-teina – older or more expert tuakana help and guide younger or less expert teina

- manaakitanga – demonstrating integrity, sincerity, and respect towards Māori beliefs, language, and culture

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles:

- Principle I: Provide Multiple Means of Representation (the “what” of learning)

- Principle II: Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression (the “how” of learning)

- Principle III: Provide Multiple Means of Engagement (the “why” of learning)

Introducing real-world problems

To get started on their makerspace projects, teachers:

- proposed real-world problems to the students

- scaffolded their understanding of authentic projects.

Students then identified their own real-life problems for projects.

Student's ideas for projects

Luke’s real-life problem: he was sick of uncomfortable headphones while wearing a hoodie

- Solution: The Sound Hood – a hoodie designed with an inbuilt speaker that laid the sound over your ears when the hood was lifted.

Hiamoe’s real-life problem: not having a phone case to fit his phone

- Solution: Learn Tinkercad to craft and design a 3D phone case using the 3D printer.

Supporting student learning

Teachers provided support during the initial stages of the students' projects. They explained the need for timelines, planning, leaders, and various roles within the group. With strong foundations established teachers then checked in with groups – some needed more frequent check-ins or support than others. Three teams had a parent come in regularly to support, teach, and connect with the children.

Students share their learning

The Toroa team held a Maker Faire, inviting parents and whānau.

The Maker Faire showcased all that the students had learnt, after 12 weeks. Students demonstrated, how the 3D printer, coding, robotics, and screen printing worked, as well as what they had created using these tools.

The students shared the ways they had:

"The children are engaged because they can see why we make it, rather than just to get a score for another test, or exam."

– Carolyn Davies, Toroa Team lead

- taken responsibility for their learning

- tested their ideas, made mistakes, and learnt in a safe-to-fail environment

- learnt about themselves as learners

- worked as effective teams

- found happiness and pride in prototyping and making something of quality to share with whānau and community in a Maker Faire and market day.

The Maker Faire extended relationships and connections with learning, while also showcasing future-focused learning within the community.

Checking the evidence

The Checking Phase of the Spirals of inquiry asks: Are we making enough of a difference? How do we know?

The Toroa team found working on real-world problems engaged students who were previously disengaged. This was evidenced by the students’:

- enthusiasm to work on their projects both in and outside the classroom

- willingness to spend time honing their craft and mastering their learning.

Students' reflection of their learning

Data from student questionnaires showed an increased level of enjoyment and recognition of successful learning.

The most enjoyable part of the project

“ The big market day, because it felt like a special gift for all the hard work we had done.”

– Marshland student

The most important thing I learned in this project

“Learning to work with different people.”

“Working with people that are not your friends, because I was more focused”

“I learnt to be better at teamwork.”

– Marshland students

Teachers as facilitators, coaches, and tinkerers

Teachers described their roles as facilitators or coaches who supported students to uncover what they needed to know for their projects. They developed an understanding of using the principles of UDL when planning to include all learners from the outset.

Projects were diverse, ranging from electronics to screen printing. Teachers learnt new things alongside their students – Ako in action.

Teachers recognise the kaupapa and skills they learnt in their inquiry are transferable.

Future focus: The next steps for the Marshland School makerspace

“From electronics and robotics, to knitting, weaving and carving, we want crafters and engineers to share their skill with our tamariki.”

Throughout the school terms, Marshlands will use their makerspace to support learning across the curriculum, integrating its use as much as possible. They will place a strong focus on the skills of communicating, listening, and collaborating. They plan to develop the Toroa daVinci Space as a community makerspace and prototype an imagination station for the juniors, with the notion of developing STEAM skills early.

Further questions identified for investigation

- How might we connect with our local community and invite them to share their skills as part of our maker community?

- How can we foster communication and collaboration between ages, generations, gender, ethnicities, and culture?

- How can we share our learning with the wider cluster network whose vision statement is "Collaborative, Connected Community – everyone preparing ākonga for the future, together"?