Distance learning at Cobden School

Tags: Distance learning | Home-school partnership | Communication | Primary |

Cobden School successfully used digital technologies to build on student learning during New Zealand’s COVID-19 lockdown.

By working together on a response, staff at Cobden school were able to create learning opportunities that supported the needs of their learners' and their whānau.

The school recognised a need to redesign their localised curriculum so that it that could:

- be delivered from a distance

- continue to reflect the school’s principles, values, and beliefs about effective learning

- maintain connections and relationships

- focus on wellbeing for all.

Where is Cobden?

Cobden School is a small school situated on the right bank of Mawheranui (the Grey River), close to Greymouth, on the West Coast of the South Island. The roll is 84 students, 27% of whom are Māori or Pacific learners. The school is decile two.

Prior to lockdown: Learning dispositions and a graduate profile

Over the last several years, Cobden staff have focused their PLD on collaborative learning using digital learning tools. While exploring collaborative learning, it became apparent some students needed support to build collaborative skills. The school planned to help students develop a positive disposition for learning and a desire to contribute to their community.

The school created a Student Graduate Profile to articulate goals for their ākonga. The graduate profile underpins all teaching and learning at Cobden, and informs strategic planning. Students who need support to meet the goals in the Graduate Profile are tracked on a collaborative “At risk register” – a spreadsheet where specific behaviours are identified, goals are set, and differentiated support is implemented for those students to make progress.

During the lockdown, teachers wanted to find a way to build on these developments while supporting learners from home.

Developing the strategy

When it became clear that schools were going to close for an extended period of time to stop the spread of COVID-19, Noula Markham, principal of Cobden School, repurposed a teacher-only day.

“We cancelled our trip to Christchurch to visit some schools, and devoted it to planning instead.”

– Noula Markham, principal

The planning day resulted in a set of guidelines and approaches to underpin all distance learning at Cobden School, which:

- was collaborative, with staff in daily contact with each other

- used what the school already had, making resources work for the home environment

- involved close contact with whānau – every family was contacted weekly with a collaborative tracking system in place to see the big picture

- had clear communication with whānau, students and staff – everyone needed to know what was going on

- focused on engagement – relationships and wellbeing were most important and teachers continued to get to know students and their whānau

- was driven by the interests of the students, and utilised resources easily found in the home to support those interests

- engaged priority learners – they were first to be contacted, and were contacted more regularly during the lockdown.

Implementing the strategy

The first 24 hours

Prior to lockdown level 4, kaiako and support staff had different roles preparing for teaching and learning without students at school.

Teacher aides assembled learning packs to send out to homes, and teachers worked collaboratively to develop distance learning plans.

Parents and whānau were contacted to offer support and reassurance. Needs were ascertained and a quick audit carried out on what resources were available in each home, such as access to an internet connection and devices.

Staff at Cobden School were already using digital tools to engage students and capture evidence of learning, such as:

- Seesaw – sharing work, commenting, messages to parents, posting activities/challenges

- Epic – setting reading books, preparation for group discussions

- Google Suite – setting work, collaborating and managing work assignments via Google Classroom

- Skool Loop, Facebook and email – communication between home and school.

Because kaiako, ākonga and whānau were already familiar with those platforms, it made sense to use them to manage remote learning. Phone calls with whānau supported those who didn’t feel equipped to support students using these tools.

Maintaining progress toward the student graduate profile

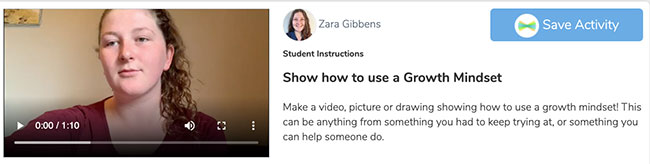

Learning tasks set for students always included challenges based on student graduate profiles. Ākonga were encouraged to explore the range of personal and interpersonal skills identified in the graduate profile. They found their own context and evidence of learning, which was shared on their digital portfolio.

Example of a graduate profile challenge

Students provided evidence of the creative ways they had cooperated with others inside and outside their bubbles, following the “Be cooperative” goal in the profile.

Building and maintaining relationships

Over the lockdown period teachers phoned students and their whānau. Teachers monitored ākonga wellbeing and interacted with them about the work they had been undertaking.

Contact with parents provided feedback on whether tasks were at the right level of challenge or if technical support was required. In some cases, teacher notes were included with activities to support parents working with their children. Teachers drew on whānau skills and enthusiasm to keep their learners engaged.

Students were sent new work each week, via Google docs, Google slides, Google classroom and Seesaw. Like most schools during lockdown, activities covered a range of learning areas such as reading, maths, science, social science, and the arts. There was always an element of choice. Ākonga were expected to engage with daily challenges by commenting, posting or liking them. Students were constantly consulted about the work they received to acertain whether it was suitable for them and enjoyable to engage with.

Kaiako filmed or recorded themselves describing an activity, reading stories or modelling their own responses to questions or activities sent to students. This helped to maintain their relationships with ākonga.

Making use of Ministry of Education resources

Aotearoa-wide activities, such as those on Papa Kāinga TV/Home Learning TV and Ministry of Education hard packs were used, but students were also encouraged to engage with school and post examples of any learning in Seesaw. Consequently, the Home Learning TV activities became a shared experience as ākonga uploaded pictures, videos, and other examples of mahi they had undertaken.

The return to classroom learning

Once the school closures from COVID-19 had ended, Cobden staff were determined not to lose their gains from the lockdown period.

- Strengthened relationships with the school community. Data shows increased family/whānau interaction with learning via Seesaw. Parents indicated they valued support from the teachers and school in their feedback.

- Increased staff collaboration. Support staff worked alongside teachers to create online learning opportunities.

- Gains in students’ digital fluency. Students successfully used a variety of apps to support learning.

- Increased digital capabilities across staff. The sharing of knowledge through the Messenger app and Zoom meetings resulted in new learning opportunities for both staff and students.

Reflecting on how their learners engaged with learning during the lockdown, teachers at Cobden decided to:

- reduce barriers and limits to the digital tools available in the classroom

- step back, and stop feeling they have to constantly lead learning.

The ability of tamariki to self-manage was a surprise to kaiako. Children tackled assigned tasks in a variety of ways. Most children were engaged in meaningful learning, and were able to explore their passions and interests. Some ākonga used digital tools that their teachers weren’t familiar with, and produced great results.

As a result, changes have been made to the way learning is planned and delivered. The most significant changes involve:

- making digital fluency a priority – Staff learned a lot of new skills over the lockdown period, and appreciated the time and freedom to explore new apps and digital tools

- de-privatising learning in the classroom – Surveys and informal discussions with the students showed that they had a strong sense of what they want learning to look like. They were happy to tell teachers what they appreciated about distance learning. Teachers are incorporating a lot more choice and agency into learning programmes, and children have been given space to run their own workshops for each other.

“It has been so exciting to see the growing partnership between children, whānau, teachers, and the school as they have received ongoing glimpses of learning via online platforms.”

– Noula Markham, principal

Cobden School looks forward to the continuing process to lift engagement and progress for students. The new-found knowledge and skills of their students will in turn inform their localised curriculum design.